|

Peace Team Details | Reports | Messages to

Diary 4 February 2003, Baghdad

Mary Foster

It is the day before Colin Powell is to give evidence

that he says will prove that Iraq is concealing

weapons of mass destruction. It is on everyone's mind

here in Baghdad - foreigners who are leaving,

foreigners who have decided to stay, Iraqis who are

leaving, Iraqis who have no choice but to stay. All

day it has triumphed in conversations as other

attempted topics have inevitably faltered and fallen

silent in the gorgon gaze of the looming war.

It is the day before Colin Powell is to give evidence

that he says will prove that Iraq is concealing

weapons of mass destruction. It is on everyone's mind

here in Baghdad - foreigners who are leaving,

foreigners who have decided to stay, Iraqis who are

leaving, Iraqis who have no choice but to stay. All

day it has triumphed in conversations as other

attempted topics have inevitably faltered and fallen

silent in the gorgon gaze of the looming war.

Today has been a very busy day, and everything about

me aches. I go through the emotions of the day:

morning's frustration with my inability to connect in

any meaningful way with an academic we interviewed;

the delight of playing with two small and exuberant

children in a new friend's home; the pain of hearing

about the war fears of people that I respect and, in

another situation, would come to know and love. And,

at the end of the day, that incomparable mingling of

joy, love and to-the-death-protectiveness that comes

with holding a baby, feeling its solid little body,

its warmth and vulnerability.

We arrived at Baghdad University in the morning and

were shown into the office of the Head of the

Department of English. The professor welcomed us with

a distancing politeness in polished and

class-establishing English. I feel rather small and

insignificant, uncomfortably noticing the food stain

on my somewhat wrinkled shirt, not an unfamiliar

feeling in such settings. Professor Abdul Sattar Jawad

introduces us to other professors and doctoral

students. I talk to an eloquent drama teacher, Sa'ad

Al- Hassani, who teaches Death of a Salesman, Waiting

for Godot, and a biography of Martin Luther I am

unfamiliar with. He draws out some of the parallels

his students are finding between these works and their

own experiences of living under sanctions and the

threat of war. As he talks, he keeps coming back to

thoughts of his older son. Now 17, his son was alone

in a car eleven years ago when an American bomb hit

the communications tower in Baghdad a short distance

from the car. When Sa'ad ran back to the car, he found

his son speechless and in shock. He didn't regain his

ability to talk for some time.

Sa'ad tells me that the boy is doing well now, a big

fan of baseball. But his war trauma has not entirely

disappeared, and last month he wrote a song about what

he went through. I ask if I would be able to get the

lyrics in English, in the hopes that a musician friend

of mine back home would be willing to put it to music.

His father looks uncertain and changes the topic.

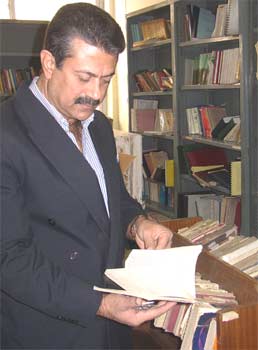

We take a little tour of the English department and

are shown the shabby library with its mutilated and

outdated books, an all too obvious metaphor for the

battering the intellectual life of Iraq has taken over

the past decade. Sa'ad tells us that he plans to

continue to teach through the war, as a simple act of

resistance, a refusal to be cowed by barbarism.

We take a taxi to our next meeting. It is our habit to

give out a sheet in Arabic explaining the Iraq Peace

Team to everyone we meet, and we choose an opportune

moment to hand it to the taxi driver. As we keep our

eyes riveted on the speeding road, he reads it and

then he bursts into the usual approval and

appreciation. I wonder if there is some amusement as

well - the smallness and vulnerability of our action

somewhat ridiculous in the face of such overwhelming

powers - but it is difficult to tell. "You very, very

good," he says, smiling broadly. As usual, we wish

that we spoke more than four words of Arabic. When we

reach our destination, he adamantly refuses to take

any payment for the ride, smiling and nodding.

Our next stop is the home of Amal, a teacher, mother

and artist. She has been a long-term friend of Voices

in the Wilderness, a warm and sparkling-eyed woman.

She welcomes us in as though we are already good

friends. She understands well what we are trying to

do, and is generous in answering our questions about

how her children are faring under the threat, how she

is preparing for the war, how the sanctions have

affected her life and work as a teacher. Her older

son, Omer, about eight years old, with his snappy hair

cut and black leather jacket, looks like a little rock

star. Her daughter Abeer wears a pink "Barbie" jumper.

All three of her children are very good looking and

love to draw. The two boys draw pictures of Jackie

Chan, bicycles, cars, tanks and soldiers. Abeer draws

fashionable women and bright-coloured flower gardens.

As they draw, Amal tells us that she can't hide

anything from the children - everyone is talking about

the coming war. Abeer is too young to remember the

time that their neighbours' house was demolished by a

bomb; the mother, grandmother and one of the children

killed. That was in 1993, when they were living close

to one of Baghdad's bridges. But she isn't too young

to understand and to feel the terror of the current

situation. Amal is planning to get out of Baghdad, to

try to weather the war in the countryside where the

bombs are less likely to find her children. She takes

the US government at their word when they say that

there won't be a safe place in Baghdad. In 1991, she

preferred to stay in Baghdad, refusing to bow to the

very real danger. But now, with three children,

everything is different.

Our next stop is the home of Amal, a teacher, mother

and artist. She has been a long-term friend of Voices

in the Wilderness, a warm and sparkling-eyed woman.

She welcomes us in as though we are already good

friends. She understands well what we are trying to

do, and is generous in answering our questions about

how her children are faring under the threat, how she

is preparing for the war, how the sanctions have

affected her life and work as a teacher. Her older

son, Omer, about eight years old, with his snappy hair

cut and black leather jacket, looks like a little rock

star. Her daughter Abeer wears a pink "Barbie" jumper.

All three of her children are very good looking and

love to draw. The two boys draw pictures of Jackie

Chan, bicycles, cars, tanks and soldiers. Abeer draws

fashionable women and bright-coloured flower gardens.

As they draw, Amal tells us that she can't hide

anything from the children - everyone is talking about

the coming war. Abeer is too young to remember the

time that their neighbours' house was demolished by a

bomb; the mother, grandmother and one of the children

killed. That was in 1993, when they were living close

to one of Baghdad's bridges. But she isn't too young

to understand and to feel the terror of the current

situation. Amal is planning to get out of Baghdad, to

try to weather the war in the countryside where the

bombs are less likely to find her children. She takes

the US government at their word when they say that

there won't be a safe place in Baghdad. In 1991, she

preferred to stay in Baghdad, refusing to bow to the

very real danger. But now, with three children,

everything is different.

We spend the early evening with a sculptor we met on

our second day in Baghdad. He is becoming well known,

but is generous with his time. He is on his way out of

the country, invited by friends to show his work in

Spain, and possibly France. We speak and joke easily

together and I soon feel comfortable enough to ask him

how he feels about leaving the country at this time. I

regret it immediately as the pain registers on his

face. All his brothers and his father are in the army,

and his mother is in Basra, close to the border where

US troops are amassed. He recalls the terror of the

first night of the war in 1991, when he was a young

teenager, huddled with his brothers in the basement of

his family home with the bombs falling around them.

They had only two gas masks among the eight of them,

and kept passing them around, each brother insisting

that the others take them. The lack of water,

electricity, food during the bombing and the immediate

aftermath; the long years of hardship afterwards. The

oil for food programme, and possibly his own success

(though he doesn't say so), finally brought respite.

But now it starts again! He is a very open person, and

his emotions show clearly on his face. I want so badly

to comfort him, but a sense of my powerlessness dries

up all my words. We sit in silence for a few moments,

and then make yet another attempt to talk of something

else.

In the evening we find ourselves in the surreal

surroundings of a sixties-style bowling alley,

swirling green walls as a backdrop to a fantastic mix

of people: our sculptor friend, the international

media, friends from Enfants du monde, MSF and other

international NGOs, Iraqi friends, an American women's

delegation all dressed in bright pink, and of course

the omnipresent Hassan, a shoeshine boy who has

practically made himself a member of the Iraq Peace

Team. It is a fund-raiser that Iraq Peace Team

members have organised for Enfants du monde and

Bridges to Baghdad. Both NGOs are struggling to

provide some relief to the children here. Their work

is heart-breaking and difficult.

Mahmoud shows up. He is a Masters student from Yemen

who was planning to get out of Iraq, but decided to

stay when he heard about the Iraq Peace Team coming to

show solidarity with Iraqis. I am moved by the

solidarity but sorry that he has put himself in

danger. He rounds up about ten of us from Canada and

the US and takes us home for dinner. Most of his other

guests are from Yemen; only one, a professor we had

coincidentally met that morning, from Iraq. The

professor has a wry smile on his face and indulges in

teasing some of the more credulous among us, playing

up to stereotypes of Muslims current in North America.

As we eat from the same plates and very literally

share bread with each other, the Yemenis open up. "Why

is the US doing this to us?" "Why do Canadians and

Americans not stop their governments from committing

these crimes?" "Don't they understand that this is

only creating a backlash?" "Our quarrel is not with

ordinary Americans, but ..."

Mahmoud lets me hold his four month year old son,

Mohammed. At this point I really have to struggle not

to cry when Mohammed happily snuggles into my arms.

Their apartment is not in a safe location. What is in

store for these good people, who are now my friends?

|