|

Peace Team Details | Reports | Messages to

Friday January 31

Baghdad, Iraq

By Manmohan (Mick) Panesar

For Iraqi intellectuals and artists, Fridays are unique in Baghdad.

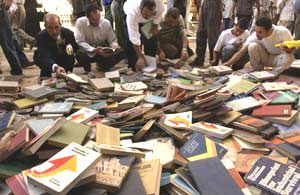

Bookseller¹s Lane, as it¹s called, has become an institution. For as long

as most people can remember thousands upon thousands of used books are put

on display along a long narrow lane in downtown Baghdad. I walk along the

lane, not sure of which side to look. On either side of the lane one can

find textbooks, novels, biographies, journals and magazines in both English

and Arabic with wide-ranging topics. At one point I stop and observe a

biography of Stalin placed next to several Agatha Christie novels and works

by Heidegger, which stand against a pile of outdated medical journals. The

variety of literature speaks to the richness of intellectual activity in

Baghdad. The vast majority of books I am perusing are pre-1980, indicative

of the effects of two decades of war and a dozen years of sanctions on

intellectual life in Iraq.

For Iraqi intellectuals and artists, Fridays are unique in Baghdad.

Bookseller¹s Lane, as it¹s called, has become an institution. For as long

as most people can remember thousands upon thousands of used books are put

on display along a long narrow lane in downtown Baghdad. I walk along the

lane, not sure of which side to look. On either side of the lane one can

find textbooks, novels, biographies, journals and magazines in both English

and Arabic with wide-ranging topics. At one point I stop and observe a

biography of Stalin placed next to several Agatha Christie novels and works

by Heidegger, which stand against a pile of outdated medical journals. The

variety of literature speaks to the richness of intellectual activity in

Baghdad. The vast majority of books I am perusing are pre-1980, indicative

of the effects of two decades of war and a dozen years of sanctions on

intellectual life in Iraq.

From some reading before coming to the booksellers venue, I know that most of

these books are personal collections that have been put up for sale. The

middle class of Iraq has been devastated by sanctions and war and many

Iraqis formerly living confortably are now put into the position of having

to sell their possessions in this case books - in order to live.

The lane is cramped as hundreds of people crowd together browsing,

conversing and bargaining. It is a beehive of activity. But the books are

expensive, $5 U.S. for an English language novel we inquired about. This is

the monthly salary for an average Iraqi worker. I think about the hundreds

of books I have in my personal collection and the endless access I have to

other books in Canada. I feel sad that these people have so little access

to the literature that many of them clearly love. My fellow IPT member Mary

meets a couple of students whose intensity and energy remind her of

activists with whome she works with back home. They express deep

frustration and despair. ³Yesterday I told my friend that I wanted to kill

myself,²

At one end of the lane is the Shah-Bender Café, a magical institution that

is transformed every Friday to a meeting place for intellectuals and artists

who gather, smoke and sip tea. Here in the café women are few and far

between. Artists, writers, poets and academics mingle, discussing topics

ranging from American cinema to Russian literature to the plight of the

Marsh Arabs in the south of Iraq. Everything except for war.

For non-Arabic speakers like me, the café provides an opportunity to engage

in rich discussions with english-speaking Iraqis. I am introduced to

Abu-Raafit, an engaging and talkative middle-aged man with a graying

moustache and beard. He works as a translator and when I asked him if he

comes here every Friday, he responds with a smile, in near-perfect English,

³No, I am here every day.² ³Many artists and teachers now work as

translators or taxi drivers to survive. Salaries are low. I work as a

translator and this is where I work.²

Our discussion focussed on his love of American culture. Nothing is

surprising here in Iraq, I think to myself. He and some of his close knit

circle adore American literature and cinema. He described a recent incident

involving one of his close friends and his favourite American writer ³We

were having our tea in the café and we mentioned to Ibrahim that there was a

copy of a new Sidney Sheldon novel on display. He ran out the door and

spent the next half an hour looking for it in the area in which we had

pointed, harrassing the bookseller. His search was in vain as there was no

new Sheldon novel. We were playing a practical joke,² he tells me laughing.

I laugh too but more because of his good-natured laugh than his story. I

imagine his frustration. New literature is almost completely absent in

present day Iraq, and as I look around the café gazing at well-dressed men

excitedly clutching, leafing through and reading at their new purchases, I

think of the teachers, artists, etc. back home. I think many of us from the

north often take books for granted.

Abu-Raafit and I continue our discussion about American cinema. He names a

few of his favourites, ³The Last of the Dogmen² starring Tom Bellinger,

³Bound² starring Jennifer Tilley, ³To Conquer a City² with Anthony Quinn,

and ³The Night of the Hunter² starring Robert Mitchum. Sheepishly, I admit

to my new friend that I haven¹t seen any of them.

I try to steer the conversation in the direction of the war and the

sanctions but he doesn¹t seem to be interested in moving in that direction.

³Whatever happens will happen. As Iraqi people we have no say in the

matter,² he tells me with a shrug of his shoulder.

When asked about whether he also loves Arab cinema, he says, ³No, I can¹t

stand it.² Why I ask, chuckling at his response. I follow up, ³But Egypt

has the third largest film industry in the world?why do you have such a

strong response²?

³Arab films have no lessons to tell. American films do,² he states as if

it¹s a fact.

If those old American classics do indeed have lessons to tell, who in the

United States is listening?

|